Restoration Work At Salernes - Reconstructing A Xth Century Chateau

Nathan Rehorick | August 2006

Introduction

For three weeks in August, 2006, I participated in a restoration camp in the town of Salernes in the region of High-Provence, France. A team of 15 volunteers with varied professional and national backgrounds, most of whom had no architecture-related knowledge, worked (primarily in french) for the APARE organisation under the direction of a technical supervisor, architect Jacques Huska, to restore parts of a Xth century chateau. This report describes the approach and techniques applied to the restoration of this building, giving a brief history of the chateau and presenting issues surrounding the work.

The Story of the Chateau

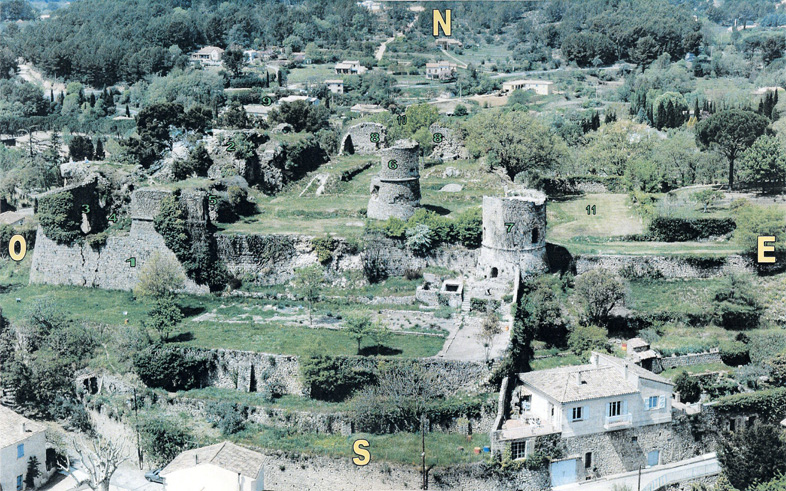

There is very little historical information available about the chateau. It is presumed to have been built in the Xth century AD, and it is known for certain to have been beseiged and captured in the XIIth century by a king named Aragon, whose family and descendants are likely to have occupied it subsequently for several centuries. Later, much of the chateau was destroyed in a fire in 1676. Whether or not any or all of it was rebuilt is uncertain but it was finally abandoned sometime in the XVIIth century due to physical degredation and the resulting inhospitable living conditions.

|

Interestingly, a lone descending heir to the property returned in the first quarter of the XXth century to try to live in the cold, leaky and un-serviced ruins, but was quickly forced to move out due to his health, which had begun to decline for obvious reasons. Unfortunately, more information about this story is unavailable as it was, like much of the chateau's history seems to have been, passed on only by word-of-mouth.

The chateau remained under private ownership for most of the XXth century but was unmaintained and continued to deteriorate. Only recently was it given over to the city council of Salernes for preservation and restoration, with the help of the APARE organiztion and volunteers.

General Context of Restoration Work

Given such a vast history of building throughout the centuries, especially in France where there is now a palimpsest of used, disused and ruined historic building sites, and given the relatively high importance that modern culture places on preserving and re-inhabiting these old buildings and monuments, there has developed a range of restorative techniques and responses. These responses vary from the cleaning and upkeep of well-used and fully functioning buildings such as great cathedrals like Notre Dame in Paris, which require the patience and eye for detail of a painter, to the jigsaw-like reconstructive work on ruins like the chateaux of southern France, which requires the more heavy-handed treatment of masons' arms and archeologists' shovels.

The project in Salernes falls under this later umbrella. The chateau's present-day condition is poor. Many walls have crumbled or are crumbling, much is overgrown with vines and small trees, and significant parts of the courtyard and other open spaces have been buried under earth and grass. Given this, the approach taken with this Chateau is to halt deterioration as quickly as possible and then move into reconstructive work with the intention of eventually reinhabiting the structure as a museum of itself.

Analysis of the Project

Drawing on a brief analysis of the architectural and physical conditions of important elements of structure as they were at the beginning of the restoration project, which was put together by our project coordinator Jacques and the first set of volunteers in the summer of 2005, areas of the site that required immediate attention versus those that could be addressed later on were identified.

|

|

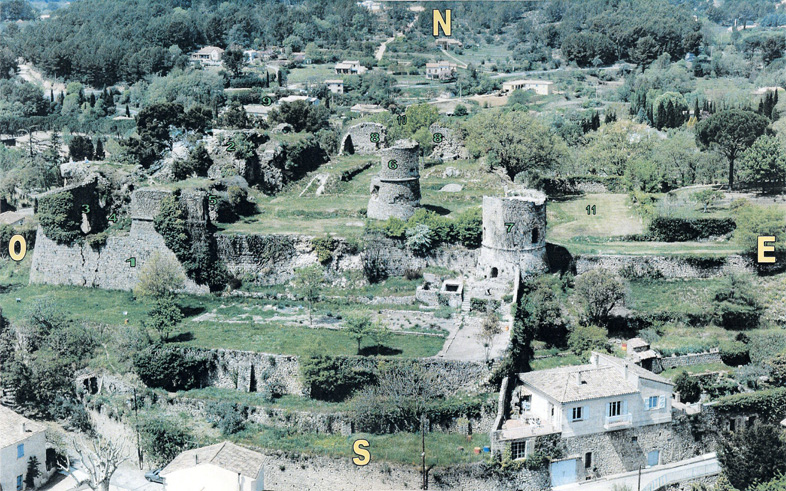

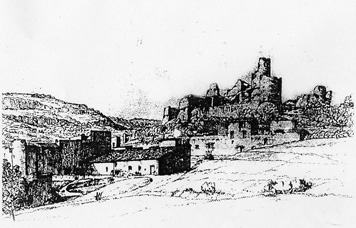

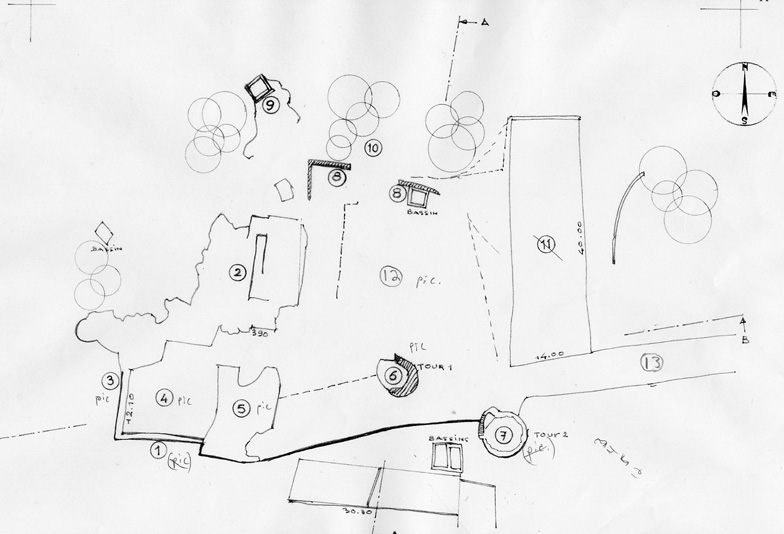

The chateau is located on the crest of a small hill that overlooks the town of Salernes to the immediate south and southwest. Three defensive walls, called ramparts, terrace up to the main level of the chateau. The original primary entrance (3), a draw-bridge located to the southwest corner of the site, would have connected directly to the town via a steep path. Currently, vehicular and pedestrian access is from a road to the southeast corner of the site that winds down to the back side of the town.

|

|

The original entrance opens onto a walled-in lower level entry forecourt (4). Here, two large vaulted spaces (5) sit side-by-side. The right-hand vault space ramps upward to a higher and primary open court space, the esplanade (12). The left-hand valuted space was likely an interior overlook post for entrance guards. While the entrance and entry forecourt walls are in quite good condition, the two vaults are in much worse shape, both having partially collapsed from both ends inward and the left-hand vault having partially caved in in the middle. The right hand vault, given its architectural uniqueness and physical fragility, was selected as the first main area of work.

Arriving into the esplanade, two towers are present. The first (6), standing alone, once served doubly as guard-tower and dungeon and is thought to have been linked by a wall to the vaulted arches to create a long and easily defensible path of entry. However, large portions of the tower had collapsed and so it was selected as the second major point of restoration work this year, picking up where the project's first volunteer group had left off.

|

|

|

Work on the second tower (7), originally found in a similar state as the first, was completed during the previous year. Other areas that were identified for immediate attention, including a small lookout post at the northwest corner of the site (9) and the crumbling rampart walls will be addressed in following years as time and funds permit.

Reconstruction Work

To begin, the worksite was setup around a mixer for making mortar. Generally, volunteers were divided into three groups. One group would mix mortar and deliver it in wheelbarrels and buckets where needed. The standard mortar recipe was two to three buckets of water from a hose mixed with a half bag of lime (about 150kg) and 10-12 shovel-fulls of sand or until the mixture reached a thick but still workable consistency. It is interesting to note that the proportions for mixes were taught on-site and in a hands-on way. Rarely would one talk about these quantities in terms of weight, but rather in practical terms such as a 'bag', a 'half-bag', a 'bucket-full' or a 'shovel-full'. Another group would gather loose stones from around the site (found around areas of collapsed structure) and chisel them into appropriate sizes to be used for rebuilding both the tower walls and the arch. A final group would be involved in the actual application of mortar or stone.

Given the different architectures of the vaulted-arch versus the crumbling tower, each required unique treatment and reconstructive techniques. Although in both cases the building elements were essentially the same (stones and mortar) they were applied in different ways.

Work on the tower had three areas of focus. The first was on sealing the edges of walls where major collapse had occurred. Using a trowel, mortar was thrown onto exposed faces where rain had washed away the original mortar and degraded the structure. Immediately after, sand or dirt collected from the site was scattered onto the wet mortar so that the dried mortar would retain a worn colour and blend in with the existing. This technique will halt degradation until the APARE team can rebuild the whole tower in years to come. Scaffolding was setup and sealing continued to the upper levels of the tower.

The second focus was on pouring a water-resistant slab on the floor of the second level. Originally, the tower was two stories above grade. However, with the eventual collapse of the uppermost floor, the first floor roof was subjected to yearly rainfalls. To strengthen the floor and protect it from water, a new mortar slab was laid ontop of the existing. For extra resistance to expansion and contraction, a small bag of polycarbonate fibres was added to each mortar mix and cement was substituted for the lime. First, the floor was cleared of any excess dirt and small shrubs that had begun to grow and was partially levelled off. Mortar, hoisted up the scaffolding by pulley, was then spread over the space, smoothed over with large flat plastic boards, and then patted down to remove excess trapped air. The slab was poured a bit higher towards the edge of the walls of the floor so as to create a gentle slope that would drain rainwater away and avoid pooling. Once the slab was fully poured and spread and the mortar had begun to dry, a bit of water was sprinkled over it throughout the day to avoid excessive cracking.

The third focus was on the patching of holes. This process involved using a trowel to apply a standard mortar mix to the edges of holes and then fitting various stones into the openings while making sure to maintain a flush surface with the adjacent existing wall. Here, as in the sealing of exposed edges, sand was thrown onto the wet mortar to blend its colour with the existing walls. Much of this task was already completed by last year's volunteers, so this job was mostly considered a touch-up.

Work on the vault had two focuses. The first was on re-building the ends of the arch back out to where they had originally been. In order to lay stones over a void, a curved formwork was built out of wood planks, was mounted on a raised metal scaffolding, and was shimmed up hug the bottom of the vault. Mortar was spread over the adjacent existing stones and a single layer of new stones was fitted into place. After drying overnight, a secondary layers of stones were laid overtop of the first to match the original thickness of the vault and to boost the arch's compressive resistance. Much attention was paid to choosing stones that were rectangular, slightly elongated and mostly flat on at least two sides so as to ensure a tight fit and proper transfer of forces from the apex of the arch laterally through each stone to the supporting walls and down to the ground.

The second focus was on pouring a water-resistant slab across the top of the vault, similar to the tower. Essentially, the same technique was used where the top of the vault was cleaned off and partially levelled out, a pumped-up mortar mix was spread across the surface and was smoothed to promote water drainage and then finally patted down with plastic palettes. A small lip was created along the inner edge of the slab to avoid water draining onto the roof of the adjacent vault. Later on, when the second vault is reconstructed underneath, the slab will be continued to cover the entire roof.

After each day, all instruments were cleaned and the smaller tools were taken off-site for safe-keeping.

The Future of the Project and Conclusion

The restoration work being done at the Salernes site at this point in time is arduously physical and, above all, imprecise. That is to say, the work is totally hands-on and very unconcerned with the finished product or details.

After the primary work of halting major degradation has been completed, probably within the first five years, a series of archeological digs will be performed in order to form a better plan of the original structure. This will setup the following phase for a more detailed overall reconstruction of the building and hopefully lead to the eventual reinhabitation of the chateau as a museum.

But, like most cultural undertakings these days, restoration work seems to be a balancing act between funding and the priorities of a directing administrative group. The project at Salernes is being supported by the town's municipal government. This, combined with the reality that the chateau has a particularly low-profile in such a small town, means that there is little invested money. The project must rely on APARE, a volunteer-based organization, for its continuation. Therefore, the work will continue in three-week sessions over perhaps as many as twenty years, if interest and a minimum of funding keeps up.

Some French Architectural Vocabulary